Bleak Horizon

( From the Chinese of Ma Chih-yuan [ ?1260 – ?1334 CE ] )

Shrivelled vines, aged trees; crows there in the dusk.

A little bridge, a dribbling stream, now someone’s hut.

An ancient road, the west wind, his emaciated horse…

past this heart-stricken man at the edge of the sky,

westward the twilight sun departs.

Clear River Song

( From the Chinese of Ma Chih-yuan [ ?1260 – ?1334 CE ] )

Woodman, astir! The mountain moon hangs low!

The old fisherman has come to call on you!

You cast aside your firewood and axe.

I’ll take my time and beach my boat.

Let’s find a cosy corner to relax!

Plum Blossom Chant

( From the Chinese of Mei-hua Ne [ Yuan: no dates available ] )

Till the end of day I searched for Spring,

but Spring could not be found,

my shoes of grass worn out by treading

the mountain-tops in cloud.

When I returned I gave a smile,

for toying with plum-blossom, smelled,

already at the branch’s end –

Spring1 Multiplied ten times!

( From my collection ‘Beneath the Silver River: Translations of Classical Chinese Poetry’ )

Note: The Yuan was the Mongol-led dynasty which ruled over China 1280-1368 CE.

The first two ‘Song-Poems’, by Ma Chih-yuan, were originally taken from Yuan period drama. The tune title of the first is Sky-Clear Sand. To accord with its uncompromisingly drear content I’ve given it the poem title which appears above (this poem I took as the basis for … to Seek, at Last, The Hollow Land which appeared very recently in The Igam-Ogam Mabinogion under the main article title Westward Walking). The title of his second, welcomingly brighter-themed poem remains that of the befitting tune-title, Clear River Song; this is one of the many early Chinese poems which extolls rustic companionship.

The third song-poem, Plum Blossom Chant, is an engaging piece which stands on its own. The poet’s name, Mei-hua Ne, translates as ‘Plum Blossom Sister’, and in the sole example I’ve come across of this poem, John Turner refers to her as ‘a Buddhist nun’, which seems appropriate and plausible enough.

Tag: poems

Westward Walking…

…to Find, at Last, the Hollow Land

A lone haggard man on a bony nag

at the beck of a dying sun,

an impoverished disc where the earth meets the sky,

a bleak eye reflected in water which lies

in every rut crowding his way –

each one with its sullen brown surface;

each one with its rim hoary-rimed.

A weak eye – but resolute, compelling him on.

And the landscape is drear, one of broken abodes,

scattered as promises along the gaunt miles.

A few bare-branched trees, mildewed blue-green,

the crows hunched upon them like ragged black lies.

He rides on, resigned, to the edge of the world

and away from a past he could never descry,

nor revise, nor relive, nor reclaim,

that he used in the one way allotted to him.

It had flickered, and faltered, and was guttering, now –

but had burned, all along, in the one way he knew.

(From ‘Memories, Moods, Reflections’ )

Do you know where it is – the Hollow Land?

I have been looking for it now so long, trying to find it again — the Hollow Land — for there I saw my love first. I wish to tell you how I found it first of all; but I am old, my memory fails me… but what time have we to look for it, or any good thing; with such biting carking cares hemming us in on every side – cares about great things… or rather little things enough, if we only knew it. Lives past in turmoil, in making one another unhappy… making those sad whom God has not made sad… what chance for any of us to find the Hollow Land?

[From ‘Struggling in the World’, Chapter 1 of The Hollow Land, an early romance of William Morris first published in The Oxford and Cambridge Magazine in October, 1856.]

…to Find, at Last, the Hollow Land is my extended rendition, modelled on and adapted from a song by the Yuan Dynasty’s Ma Chih-yuan (c.1260 – c. 1324 CE).

Oh, you Big Beast!

A Sunnit to the Big Ox

(Composed while standing within two feet

of him, and a’tuchin of him now and then.)

All hale! thou mighty annimil – all hale!

You are 4 thousand pounds, and am purty wel

Perporshund, thou tremendjus boveen nuggit!

I wonder how big yu was when yu

Was little, and if yure mother would no yu now

That yu’ve grone so long, and thick, and fat;

Or if yure father would rekognise his ofspring

And his kaff, thou elephanteen quadrupid!

I wonder if it hurts yu much to be so big,

And if yu grode it in a month or so.

I spose when yu was young tha didn’t gin

Yu skim milk but all the creme yu could stuff

Into yore little stummick, jest to see

How big you’d gro; and afterward tha no doubt

Fed yu on oats and hay and sich like,

With perhaps an occasional punkin or squosh!

In all probability yu don’t know yu’re anny

Bigger than a small kaff; for if yu did

Yude break down fences and switch yure tail,

And rush around and hook and beller,

And run over fowkes, thou orful beast.

O, what a lot of mince pies yude maik,

And sassengers, and your tail,

Whitch can’t weigh fur from forty pounds,

Wud maik nigh unto a barrel of ox-tail soup,

And cudn’t a heep of staiks be cut off you,

Whitch, with salt and pepper and termater

Ketchup, wouldn’t be bad to taik.

Thou grate and glorious inseckt!

But I must close, O most prodijus reptile!

And for mi admiration of yu, when yu di,

I’le rite a node unto yure peddy and remanes,

Pernouncin yu the largest of yure race;

And as I don’r expec to have half a dollar

Again to spair for to pay to look at yu, and as

I ain’t a dead head, I will sa, farewell.

Anon. (19th century).

A small glossary for the more likely problem words:

sunnit: ‘sonnet’, though obviously here not pertaining to the prescribed poetic form of 14 lines. It refers to another more general and less frequent usage meaning simply a ‘little song’

tha didn’t gin: ‘they didn’t give’

a node: ‘an ode’

peddy: At first I thought it could mean a ‘paddock’, an enclosure for horses, cattle, and other large animals, a ‘pad’ being a path on which to roam. In ‘paddock’, the word generally used, the ‘-ock’ serves as a diminutive suffix, as in, e.g., (and aptly here) ‘bullock’. Or … ‘pedigree’? That’s a possibility. ‘Body’, too, would make sense; on the whole, I’d go for that. Any suggestions?

A neat poem, I thought. Witty. The language used is funny. Now I wish I’d used ‘yu’ / ‘yu’d’ etc., in Revenge of the Black Dog, just recently posted, and I’m thinking of going back and doing just that.

I found this ‘Big Ox’ poem in an old collection, undated but from the cover decoration typical of the 1920s, and a time when it was ‘the thing’ to fiddle about with spelling in comic verse. It’s an English publication, and I thought that the ‘countrified’ style must indicate the deepest English farming south, Bedfordshire’s green spreads or thereabouts. I expected it to be that. But on a second reading, there were plain signs that it was American (the mentions of pumpkin and squash – not unknown in England, admittedly, but decidedly more popular in America – tomato ketchup, half a dollar, and a term such as ‘dead head’). So then I paid closer attention and took proper notice of the ‘purty’, the ‘kaff’, the ’spose’, the ‘beller’ and the ‘fur’. The ‘purty’ with its re to ur metathesis stood out, and the ‘kaff’ with its short vowel clinched it as a poem from across the Atlantic. As to the words first mentioned, I took a look at what I have on etymologies / archaic language / historical slang, etc. (always leaving The Great God Google as a very last resort, otherwise why did I buy these tomes years ago? ‘What’s the point of owning a mace if you don’t use it?’), discovering that tomato ketchup was concocted first in America as early as 1812, and that deadhead (a term new to me), having the meaning of a person who hasn’t paid for an entrance ticket and therefore eminently suitable as it appears in the closing line, originated in the USA in 1849, becoming anglicized c.1864. In the course of time words naturally travel in more than one direction. I’d venture to place this lovable contribution to humorous verse around the third quarter of the 19th c.

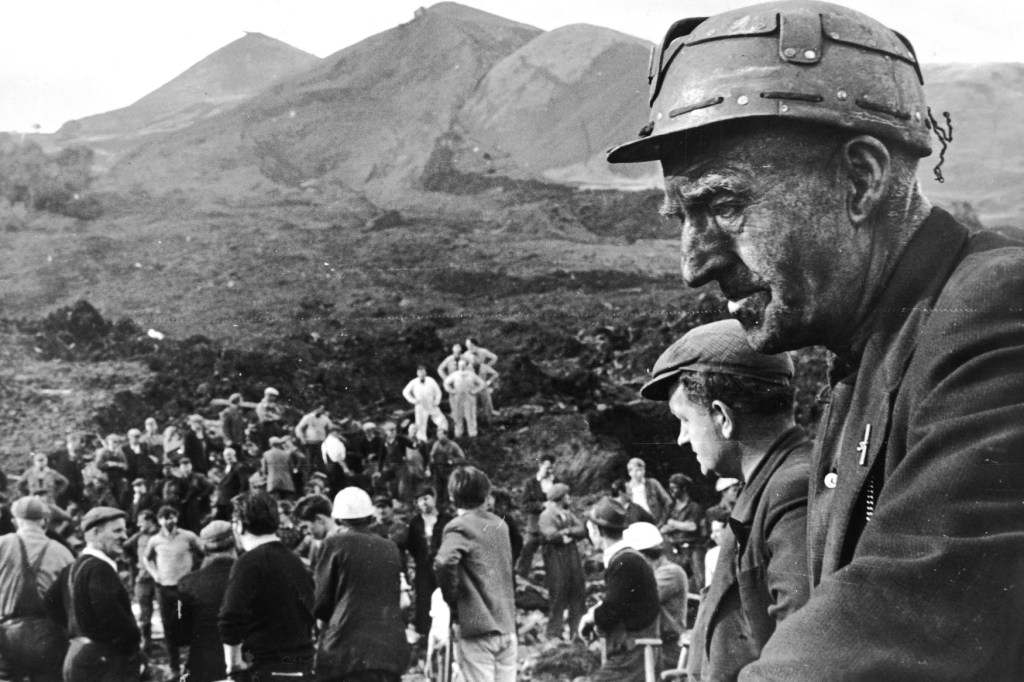

A Song for Aberfan

Aberfan: A single word, the name of a small village in the county of Glamorgan, Wales, which will bring immediately to mind, not only to we who are Welsh, but to millions worldwide, a single tragic picture – that of the great deluge of black slurry which at 9.13 a.m. on the morning of 21st October, 1966, slid down a hillside, engulfing everything in its path and cutting short the lives of 144 people, most of them children, as they began a new day. It is a name and an event printed indelibly on so many minds, that day on which a colliery spoil tip perched high above Aberfan stirred its unstable roots and sent a torrent of more than 150,000 tonnes of coal waste tumbling upon the village school and part of a row of houses. Here, guest-poet Gwyn Owen looks back upon the tragedy after some forty years had passed and with the lyrics of his song, Come Dance Away The Shadows, paints an inspirational picture in words. Gwyn is a writer of short stories, poems, songs, and plays. He has also written a screenplay and a young-adult novella. From his own memories, especially of that day on 21st October, he tells us:

‘I was born in Pontypridd, a town a few miles south of Aberfan, as were my parents. We left there for the then new town of Cwmbrân when I was three. But, as most of my relatives continued to live in and around Pontypridd, I visited often and always had a strong emotional attachment to the area. I was thirteen when the shadow of the Aberfan disaster darkened our lives. I will always remember how I heard of the tragic events for the first time. I was off school on the day (the half-term holidays were different in Cwmbrân and Aberfan) and that morning, my mother, as she often did, was listening to the radio. It was the BBC Home Service, which in those days broadcast through the medium of Welsh for a couple of hours a day. Although I was aware my mother listened to the Welsh broadcast, I had no Welsh myself, so paid little attention to the fact. I remember asking my mother something and her ignoring me, instead, turning to the radio and listening a little more intently. I asked my question again, a couple of times, before my mother turned to me and snapped ‘Shut up!’. Snapping at me was something she never did. Shocked, I watched her turn toward the radio again, listening intently. The tears slowly started to trickle down her cheeks. She didn’t stop crying for a few minutes, unable at the time, to tell me what she had heard. What has stayed with me ever since was, of course, the news of the tragedy itself; but also the fact that I was unable to understand my own language’.

Before coming to Gwyn’s poem, a brief overview of what others have said: because much has been written of the Aberfan disaster in verse. Notably, among others in Welsh, are poems by D. Gwenallt Jones and T. Llew Jones. In English there has been a good deal more – poems by natives of Aberfan who were there on the day, some of them relatives who, when the cataclysm came, were working their shifts underground; poems by later witnesses who assisted with the rescue operations and others, natives and strangers, who many years later were moved to put pen to paper – score upon score of all of these, from which collections have been made and published. Not many of whom wrote these were accustomed to their undertaking; but what is visible in them, as individual expressions of care and grief, is their deep heartfelt sincerity. Practised poets, also in their varying degrees of ability and technique, have made their contributions; there were ‘commissions’ to write poems for the magazine-media; similarly there were the sponsored projects of arts foundations. People are composing verse on the tragedy to this day. And for those who were most fully impacted by what occurred at Aberfan, those families which lost their loved ones on that October day, the story was to be drawn out – in the Tribunal Inquiry of the following year, and its unsatisfactory and questionable repercussions which dwell still in Welsh minds. [For succinctness, perhaps the best assessment of the legalities of the situation regarding corporate responsibility is ‘All the elements of tragedy were there’posted by Environment, Law, and History on October 24, 2016. The title is a variation of the refrain from Keidrych Rhys’ poem Aberfan: Under the Arc Lights ].

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Come Dance Away The Shadows

In the quiet of the evening I hear their voices call

Come dance away the shadows one and all

Watch the fortress crumble and the highest mountain fall

Come dance away the shadows one and all

In the quiet of the evening their spirits walk abroad

Dancing with the spirit of their Lord

They offer you no promises that morning sun can’t keep

And dance away the shadows as you sleep

They call like children playing from a summer meadow green

They dance and sing like time has never been

All memory has faded and tomorrow never comes

And dance away the shadows one by one

You who fear the demons with hatred in their eyes

The prophets with their sermons and their lies

Hear the whispered voices of the children as they call

Come dance away the shadows one and all

Out there in the forest they evil shadows steal

And knowingly sing ‘all who suffer heal’

The lamb will tame the lion and the tyrant with his gun

And dance away the shadows one by one

In the quiet of the evening I hear their voices call

Come dance away the shadows one and all

Watch the fortress crumble and the highest mountain fall

Come dance away theshadows one and all

Gwyn Owen

© 2024 Gwyn Owen. All rights reserved

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Those who have read a fair portion of the probably hundreds of poems inspired by Aberfan will like as not conclude that the majority present stark, emotive narratives evincing all the sorrow, devastation and helplessness surrounding this unbelievably horrific disaster, ‘Why?’ ‘Why?’ is the unavoidable, omnipresent question asked by the authors of these poems, and struggle to answer in their various ways. Speaking of his lost son, one of the many moved to record their feelings in verse says: ‘He is out playing somewhere’. And it can indeed be said that when we lose a loved one, they never quite seem gone, but perhaps somewhere hidden from us, as we are hidden from them, and they exist always in our thoughts, exactly as we remember them. We, far away now in time and many of us in distance, cannot truly know the suffering following that day. How in heaven’s name can those who were directly affected come to terms with what happened? Some illusory, hardly conceivable measure through which a kind of conciliating chapter may be reached must be all there was and is to hope for.

Come Dance Away The Shadows takes a singular approach to this grief. As a song it has a harmony drifting through it which carries us to and among the lost children, yet away from a heaviness of thought. It might occur that the picture is very much like another, and one we all know, concerning children taken into a hillside – those said to have been following the piper’s tune in the village of Hamelin seven hundred years ago. This has been noted before; it is a feature of T. Llew Jones’ Welsh poem mentioned above, and has been again noted by others in the mass of Aberfan poetry. The parallel is a relevant and poignant one, from the number of children – 130 in Hamelin – in that the German account is thought to be based on an actual event, and in that the children were taken by the mountainside. It is as though, in Gwyn’s song, the children are calling out to us in reassurance; they will dance away the shadows left on their loved ones’ and remaining lives ‘as we sleep’. In two of the later stanzas there is a note of unease, a sombre note which might lead us to the thought that their passing was indeed avoidable; or perhaps a reminder of how little account the demons which sometimes inhabit adult minds, when all life and love is taken into account, need be. The song is a gentle calling, and we are asked to listen for the voices in the hope that in our recollections we can know a child’s peace.

The Sixty-six Distillations

‘Distillations’ – These are Haikuform pieces, brief three-liners intended to express the core essence of a subject through using the most minimal sequence of words. The main heading of the article says there are sixty-six, and as it has a nice sound to it the title has been kept, although I see that on the last count there were seventy-seven; it’s possible that by now, a good while later, there are eighty-eight. The sixty-six and the nine or ten additions were written within a short period toward the end of last year and the beginning of this, when circumstances determined that my poetry-posting field should lie fallow awhile. I must have over five-hundred of these ‘distillations’ altogether; but ’the sixty-six’ were fresh recruits hurriedly mobilized to serve in an interim February article – and now it’s June. [*Of the main five-hundred, sixteen were posted under the title Medley: The Sounds, Silance, and Scenes of Open Spaces in the Aug.-Oct. 2022 section of ‘The Ig-Og’]. The term ‘distillations’ I borrowed from Clark Ashton Smith, who assisted Japanese literateur Kenneth Yasuda in his superlative study of traditional Japanese Haiku in the West, and which persuaded Smith to experiment further with minimal forms. ‘Haikuform’, ‘Haikuesque’, ‘Haikutype’ … anyone who is fully acquainted with traditional Japanese Haiku will soon see that the majority of the short pieces which appear below are not at all Haiku in the 17-syllable 5-7-5 arrangement (which continues to persist among a fair number of English language Haiku aficionados) although some may either by serendipity or with overall result in mind fall in with the pattern. Many of them, though, do conform to some of traditional Haiku’s more important – and for effect very necessary – conventions. Traditional Japanese Haiku’s adaptation into an English-language setting has not come without various transformations.

Minimal poetry demands that a great deal must be concentrated in a very small space, and a successful, truly effective economy of words is not all that easily attained. Some of those below will be seen as less successful than others. Before dipping in, then, as I hope you will, I’d just like to say this about these short and simple-seeming poems: Many of the topics are very ordinary, it’s agreed; but how often do we home in upon the core dynamism of an ordinary moment, actually take hold of it and weigh our thoughts, or half-thoughts, or fleeting sensations, or those of any passing, mundane happening? The crystallization of such moments – their intrinsic, unexpressed meaning most often overlooked – is what these short pieces are about. Some, no doubt, even with this as a goal, fall short of the mark: others, those outside the immediately experiential, such as those wholly imaginary or of flippantly humorous intent, can be seen as foxes in that fold; but If just a small number of the ’sixty-six’ cause you either to knit your brows contemplatively for a second or so, or raise a small smile, or give you the feeling of ‘Yes, that’s how is’, then I feel those will have succeeded.

Now and again in these posts I’m prone to include a word – most often a name – which by virtue of its outlandishness and hopefully its unfamiliarity to most is calculated to puzzle, the strategy being to propel the inquisitive into an impassioned investigation of the obscure (‘Victor’ and his geometric smile will almost certainly be well-known enough to be dismissed this role). Bowing, now, to a superstition about favourable and unfavourable numbers and at a final count having seen that there were indeed an inauspicious eighty-eight of these ‘distillations’, I’ve looted the original five-hundred for a further few in order to hurriedly head for ninety-nine. But just to be on the safe side – Dalmatians.

****************

Journeyman

The Shadow’s chasing you.

You have to move!

Find, poor fool, your love.

Neighbours

Mrs.Black meets

Mrs.Brown. Eyes

in every window spy.

Looking Back

Patches of sunlight.

Chances not taken – Piper, please!

A different tune …

Autumn Evening

Fields, trees, houses

stand out stark, till … gone!

The night takes hold.

Studying the Flames, and Thinking

Nice, by the fire.

Glad I’m not in it,

tied fast, screaming.

Travellers

We drift into sleep …

closed shadow-world. While Earth

ploughs deep through the void.

Loan

Winter sun

just setting – lends fire

to my face.

Roof

Cat lies on the tiles …

all swaying tail

and cunning eyes.

Accomplice

Night’s cloak, party to

the trysting of all lovers …

and all rogues.

Lost in France

School French? The natives

twig it! Why’d they reply

in rapid gibberish?

Clocktor’s Orders

My clocktor says

to get some sleep.

My book says not.

Not Invited

‘It’s really warm’,

winks the clock to the fire.

Rain hammers at the panes.

Paramour

Print’s dancing.

Please, a para more before …

Book’s on the floor.

Gatherings

We sit; we laugh.

Loved tales repeat. But

daylight hovers to go.

Ingrates?

I treat my books

respectfully. But do they care

a toss for me?

Ecstasy

Picking bogies

in the sun. Flicking them

at everyone.

Gion Geisha

Samisen

sedately tinkles. Sensual

Geisha giggles.

Not Fair!

Clocks tick in the dark.

Oi! While we’re asleep?

They gaily squander time?

Light Sketch

Grey pencil strokes

upon the world. And dawn

comes timidly.

Uprising

Ashes getting restive.

Nothing that a taste of flame

won’t tame.

Fearsome Me

Angry, swearing,

stamping upward … !

Each stair trembles.

Old Violin

Dust-filled attic…

Silence reig – Plaaanng!

Too-tautly-strung.

Bedtime Challenge

Turn off the light.

Face, fool, the secret

terrors of the night.

Spirit Moon

Mist-covered moor.

November Moon’s a

pale masked pearl.

Indifference

I spoke into the fire

of my plight. Damn flames

laughed heartily.

Herald

Quiet dawn.

Stars swept away. Then …

throbs on the horizon.

Old Garden

There, against mellow

lichened red of brick … Rich

orchard burdens ripen.

Surprise

The chisel chips. My

name’s being writ! Okay … I’ll

lie here for a bit.

Interruption

Grandfather Clock swung

tick and tock. ’Twas Time stopped

still the pendulum.

Lieutenancy

The curate comes,

subauditum – the clergy’s

duteous subaltern.

Display

Coins on

a collector’s velvet blue.

So lie the stars tonight.

Incoming

An imploration,

sky. Let me just

get home in time!

Wasted

Yes, there was the thing

called Youth. Summers

were much longer, then.

The Shortest Distance

I smiled. She smiled.

It was exactly

as good Victor said.

Interval

November’s emptiness …

The playground

when the bell has gone.

Entering the Glade

Sun strikes.

Russet shall be topaz,

Green? Why, emerald!

Rising

Near ruling Moon,

Venus, kindling silver,

wakens.

Encroachment

Writhings, small,

in glowing caves, till –

solid logs, ablaze.

Development

Happy old houses …

staring with regret

on change.

Sunday

Bells summon all.

Rooks flap and caw, all unaware

of Sunday.

All in Black

Jackdaw processions

up chapel hill? Well, I dunno,

sez Mr. Crow.

Roofscape

Streets lie shrouded.

Moonlight’s searching

roofs and chimneys.

New Llanelli

The good old town

still speaks to me … though not

to my heart anymore.

Timidity

Roomful of anger,

quarrels and shouts. Clock,

alarmed, ticks quietly.

Something to Say

Cold distance. Chill glarings

fill the room. How rude,

that deafening tick and tock!

Neighborhood Moon

Take care, you million

glitterers! The reaper’s

sickle’s poised!

Clock

The fateful finger points

and says ‘Remember!’.

Us? We giggle on.

Faint

He calls

to his dogs. The hunter who

has passed beyond the brow.

Pick and Catch

Leave flowers and butterflies

alone.

The world’s too fair. You hear?

The Compleat Astrophysicist

Once, they say, was

a great big bang. But

nobody there to tell …

Time Out

Back in The Big Bang

seconds were sent sprawling.

Clocks soon captured them.

Escapade

Firelight leaps to

ceiling’s corners. Escape

the room … ? No, no.

Seventeen Years

My brave old dog

gazed up at me … Oh! I could see

his spirit gone!

Restless

I couldn’t sleep.

The night passed by. It took

about a year.

Earthbound

Icarus, hurtling

past his dad:

‘Shut up about the Sun!’

Fireside Quiet

Firelight and silence.

A murmur, an answer.

The falling of an ember.

Play

Children clamber

in a tree. Two bump heads –

laugh helplessly.

The Defence

Draught’s brisk!

Candle-flames! Aux Armes! Stand fast

upon your wicks!

Winter’s Eve

A glow and crackling logs

within. Without

all’s chill and dumb with snow.

The Bright Side

Smile when you pay

the ferryman. He who looks like

Nosferatu.

Cares

Wind dies – then

rises; slaps me in the face.

Like hope.

Waiting

Night’s almost done.

Above, the scattered stars pale,

expectant of the sun.

Thingness

All’s a kindled fire

in every state. So stir the coals

with care.

Young Moon

Lazy Miss,

on her back, napping in

her hammock …

Desiderata

Laugh, yes, and be merry.

Be kind; show love.

Time is an outstretched hand.

Assault

Willow heaves her load

against the wind.

She’ll not give in.

The Poker’s Touch

The Master Log’s upon

the embers. The poker’s touch.

A merry blaze.

It’s Hot

Damn hot! Sleeping cats’ll

fall off windowsills. Great toads’ll

die of thirst.

Night Watch

Night waters. So, you stars?

Look down upon yourselves!

So many millions deep!

Tiddler

Ten million scattered stars

shine. Damn! My puddle’s

caught just one!

Imagination?

Dark street.

My footsteps. They sound like…

footsteps following.

Damascened

Spied, through the crowd,

a shapely, dazzling ecstasy!

Floored like Saul – that’s me.

Diadem

Gorse tops

the mound. A sleeping warrior’s crown

of gold.

What they Boast About in Valhalla

‘And last I clove the mantichore

his head. He rained hot gore.

And thus I burned and bled’.

Lull

When table-talk stops short –

that weird moment’s silence!

All swap smiles.

Journey

The lame child

limps and lingers. The lane

runs on.

Diminishing

Talk at twelve; logs spit.

Murmurs at three; red segments.

Four o’clock – the parting.

Sol Invictus

Scorching in the

veg patch. Heat waves skip along

the cabbages.

The Armada

Washing’s at hoist.

Ballooning blouses!

Knickers ahoy!

Ode to the Sun

Yield, glorious orb of gold,

go down … Don’t take

too long kow-towing, eh?

Koshtra Belorn

Her matchless contours …

created solely to compel

men’s adulation.

Glee

A silly little thing.

But our eyes met – and we laughed,

and laughed again!

Thoughts

There the mountains, there

the sea; the great sky … the

dot of life that’s me.

Linings

Soft stuff lines

li’l warblers nest: As it does

the big bad hawk’s.

Alchemy

A world once beautiful …

Transmuted thus

by wars and lust!

The Silence from Horeb

We know you like

to hide your face, but – God!

To look away!

Moody

Grate’s deep in ashes.

Embers, few. Blow on them.

They’ll glow.

Lemme Alone!

A hermit’s life for me,

I swore: Uh-oh. Not so, thought

he girl next door.

Master Rat

Young rat’s small, yet.

But, bold? Cares not a jot

for etiquette!

Small Suns

A sunless alley’s

end. There, though,

dandelions glow.

Vacant

A small house, frail,

unoccupied.

The snail long gone

Hesperides

The veil slips:

Lifts life’s colours from all

earthly things.

Stealth Merchant

Thrush, on the wall,

sings joyously. Below glides Tom,

with evil eye.

Alone

Nightfall – time

of mockeries. That tree? Those rocks?

Grim fantasies!

Ongoing

Rain beats a rhythm

to the old clock’s tick. Dark blood

courses through my veins.

Play, Weigh

As years go by

come imps

to play upon the mind.

Blackberry Picking

Lazing in the sun

high and out of reach

the best ones hung.

Those Summers

Young, standstill summers

those, my love! But the days

were running away.

Naked Moon

Keen wind unwinds

her cloud-wraps, and, undressed,

the goddess smiles.

Youth

Live, lads and lasses – now!

Heed not

the hungry ticking of the clock.

Home

The place wells up within me,

now. Like a lost love’s

whispering still.

F I N I S