…to Find, at Last, the Hollow Land

A lone haggard man on a bony nag

at the beck of a dying sun,

an impoverished disc where the earth meets the sky,

a bleak eye reflected in water which lies

in every rut crowding his way –

each one with its sullen brown surface;

each one with its rim hoary-rimed.

A weak eye – but resolute, compelling him on.

And the landscape is drear, one of broken abodes,

scattered as promises along the gaunt miles.

A few bare-branched trees, mildewed blue-green,

the crows hunched upon them like ragged black lies.

He rides on, resigned, to the edge of the world

and away from a past he could never descry,

nor revise, nor relive, nor reclaim,

that he used in the one way allotted to him.

It had flickered, and faltered, and was guttering, now –

but had burned, all along, in the one way he knew.

(From ‘Memories, Moods, Reflections’ )

Do you know where it is – the Hollow Land?

I have been looking for it now so long, trying to find it again — the Hollow Land — for there I saw my love first. I wish to tell you how I found it first of all; but I am old, my memory fails me… but what time have we to look for it, or any good thing; with such biting carking cares hemming us in on every side – cares about great things… or rather little things enough, if we only knew it. Lives past in turmoil, in making one another unhappy… making those sad whom God has not made sad… what chance for any of us to find the Hollow Land?

[From ‘Struggling in the World’, Chapter 1 of The Hollow Land, an early romance of William Morris first published in The Oxford and Cambridge Magazine in October, 1856.]

…to Find, at Last, the Hollow Land is my extended rendition, modelled on and adapted from a song by the Yuan Dynasty’s Ma Chih-yuan (c.1260 – c. 1324 CE).

Tag: welsh-poetry

Helionaut

The Lament of Icarus

(From the French of Charles Baudelaire )

The lovers of ladies of the night

are hale and hearty, nicely liked.

While as for me… my embrace was smashed

by cloud-shapes which I tried to grasp.

Because of the matchless astral lights

which blaze where innermost heavens teem

there was nothing more for my blinded eyes

of its suns than a fast-receding dream.

In vain did I search in the whole of space

for a centre or an end,

and I know not under what fiery gaze

I felt my pinions rend –

and my crave for beauty blasted me!

The honour, sublime, shall not be mine

of giving my name to the endless deep:

My tombstone there was already assigned.

Les Plaintes d’un Icare

Les amants des prostituées

Sont heureux, dspos et repus;

Quant à moi, mes bras sont rompus

Pour avoir étrient des nuées.

C’est grâce aux astres nonpareils,

Qui tout au fond du ciel flamboient,

Que mes yeux consumés ne voient

Que des souvenirs de soleils.

En vain j’ai voulu de l’espace

Trouver la fin et le milieu;

Sous je ne sais quel oeil de feu

Je sens mon aile qui se casse;

Et brûlé par l’amour du beau,

Je n’aurai pas l’honneur sublime

De donner mon nom à l’abîme

Qui me servira de tombeau.

(From: ‘Of Gods and Men’)

Note: Readers may also like to look at the longer Daedalus Alone, (not a translation), posted on The Igam-Ogam Mabinogion Nov. 2019 – Jan. 2020.

The article’s title, Helionaut (‘Sun Voyager’) reaches us, of course, through the family line of the redoubtable crew of the Argo – aeronaut, astronaut, cosmonaut – the ‘helio-‘ taken in turn from Greek helios, ‘sun’, and the name of the Greek sun-god. Welsh haul is cognate, both being derived from the same Proto-Indo-European root. There are cognates in other European languages, e.g., Latin sol (which might seem somewhat removed from helios, but not so from the original Proto-Indo-European) as in Sol Invictus (‘Unconquerable Sun’) the name of the official Roman sun-god during the Later Empire. But none of these cognates are so agreeably close to the Greek as the Welsh.

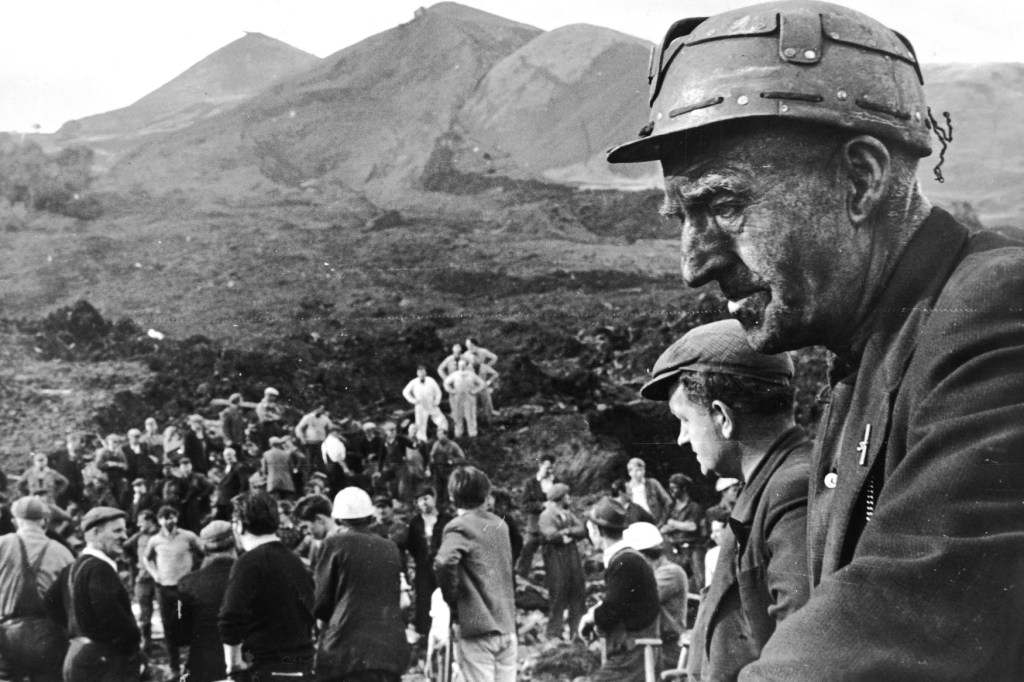

A Song for Aberfan

Aberfan: A single word, the name of a small village in the county of Glamorgan, Wales, which will bring immediately to mind, not only to we who are Welsh, but to millions worldwide, a single tragic picture – that of the great deluge of black slurry which at 9.13 a.m. on the morning of 21st October, 1966, slid down a hillside, engulfing everything in its path and cutting short the lives of 144 people, most of them children, as they began a new day. It is a name and an event printed indelibly on so many minds, that day on which a colliery spoil tip perched high above Aberfan stirred its unstable roots and sent a torrent of more than 150,000 tonnes of coal waste tumbling upon the village school and part of a row of houses. Here, guest-poet Gwyn Owen looks back upon the tragedy after some forty years had passed and with the lyrics of his song, Come Dance Away The Shadows, paints an inspirational picture in words. Gwyn is a writer of short stories, poems, songs, and plays. He has also written a screenplay and a young-adult novella. From his own memories, especially of that day on 21st October, he tells us:

‘I was born in Pontypridd, a town a few miles south of Aberfan, as were my parents. We left there for the then new town of Cwmbrân when I was three. But, as most of my relatives continued to live in and around Pontypridd, I visited often and always had a strong emotional attachment to the area. I was thirteen when the shadow of the Aberfan disaster darkened our lives. I will always remember how I heard of the tragic events for the first time. I was off school on the day (the half-term holidays were different in Cwmbrân and Aberfan) and that morning, my mother, as she often did, was listening to the radio. It was the BBC Home Service, which in those days broadcast through the medium of Welsh for a couple of hours a day. Although I was aware my mother listened to the Welsh broadcast, I had no Welsh myself, so paid little attention to the fact. I remember asking my mother something and her ignoring me, instead, turning to the radio and listening a little more intently. I asked my question again, a couple of times, before my mother turned to me and snapped ‘Shut up!’. Snapping at me was something she never did. Shocked, I watched her turn toward the radio again, listening intently. The tears slowly started to trickle down her cheeks. She didn’t stop crying for a few minutes, unable at the time, to tell me what she had heard. What has stayed with me ever since was, of course, the news of the tragedy itself; but also the fact that I was unable to understand my own language’.

Before coming to Gwyn’s poem, a brief overview of what others have said: because much has been written of the Aberfan disaster in verse. Notably, among others in Welsh, are poems by D. Gwenallt Jones and T. Llew Jones. In English there has been a good deal more – poems by natives of Aberfan who were there on the day, some of them relatives who, when the cataclysm came, were working their shifts underground; poems by later witnesses who assisted with the rescue operations and others, natives and strangers, who many years later were moved to put pen to paper – score upon score of all of these, from which collections have been made and published. Not many of whom wrote these were accustomed to their undertaking; but what is visible in them, as individual expressions of care and grief, is their deep heartfelt sincerity. Practised poets, also in their varying degrees of ability and technique, have made their contributions; there were ‘commissions’ to write poems for the magazine-media; similarly there were the sponsored projects of arts foundations. People are composing verse on the tragedy to this day. And for those who were most fully impacted by what occurred at Aberfan, those families which lost their loved ones on that October day, the story was to be drawn out – in the Tribunal Inquiry of the following year, and its unsatisfactory and questionable repercussions which dwell still in Welsh minds. [For succinctness, perhaps the best assessment of the legalities of the situation regarding corporate responsibility is ‘All the elements of tragedy were there’posted by Environment, Law, and History on October 24, 2016. The title is a variation of the refrain from Keidrych Rhys’ poem Aberfan: Under the Arc Lights ].

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Come Dance Away The Shadows

In the quiet of the evening I hear their voices call

Come dance away the shadows one and all

Watch the fortress crumble and the highest mountain fall

Come dance away the shadows one and all

In the quiet of the evening their spirits walk abroad

Dancing with the spirit of their Lord

They offer you no promises that morning sun can’t keep

And dance away the shadows as you sleep

They call like children playing from a summer meadow green

They dance and sing like time has never been

All memory has faded and tomorrow never comes

And dance away the shadows one by one

You who fear the demons with hatred in their eyes

The prophets with their sermons and their lies

Hear the whispered voices of the children as they call

Come dance away the shadows one and all

Out there in the forest they evil shadows steal

And knowingly sing ‘all who suffer heal’

The lamb will tame the lion and the tyrant with his gun

And dance away the shadows one by one

In the quiet of the evening I hear their voices call

Come dance away the shadows one and all

Watch the fortress crumble and the highest mountain fall

Come dance away theshadows one and all

Gwyn Owen

© 2024 Gwyn Owen. All rights reserved

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Those who have read a fair portion of the probably hundreds of poems inspired by Aberfan will like as not conclude that the majority present stark, emotive narratives evincing all the sorrow, devastation and helplessness surrounding this unbelievably horrific disaster, ‘Why?’ ‘Why?’ is the unavoidable, omnipresent question asked by the authors of these poems, and struggle to answer in their various ways. Speaking of his lost son, one of the many moved to record their feelings in verse says: ‘He is out playing somewhere’. And it can indeed be said that when we lose a loved one, they never quite seem gone, but perhaps somewhere hidden from us, as we are hidden from them, and they exist always in our thoughts, exactly as we remember them. We, far away now in time and many of us in distance, cannot truly know the suffering following that day. How in heaven’s name can those who were directly affected come to terms with what happened? Some illusory, hardly conceivable measure through which a kind of conciliating chapter may be reached must be all there was and is to hope for.

Come Dance Away The Shadows takes a singular approach to this grief. As a song it has a harmony drifting through it which carries us to and among the lost children, yet away from a heaviness of thought. It might occur that the picture is very much like another, and one we all know, concerning children taken into a hillside – those said to have been following the piper’s tune in the village of Hamelin seven hundred years ago. This has been noted before; it is a feature of T. Llew Jones’ Welsh poem mentioned above, and has been again noted by others in the mass of Aberfan poetry. The parallel is a relevant and poignant one, from the number of children – 130 in Hamelin – in that the German account is thought to be based on an actual event, and in that the children were taken by the mountainside. It is as though, in Gwyn’s song, the children are calling out to us in reassurance; they will dance away the shadows left on their loved ones’ and remaining lives ‘as we sleep’. In two of the later stanzas there is a note of unease, a sombre note which might lead us to the thought that their passing was indeed avoidable; or perhaps a reminder of how little account the demons which sometimes inhabit adult minds, when all life and love is taken into account, need be. The song is a gentle calling, and we are asked to listen for the voices in the hope that in our recollections we can know a child’s peace.