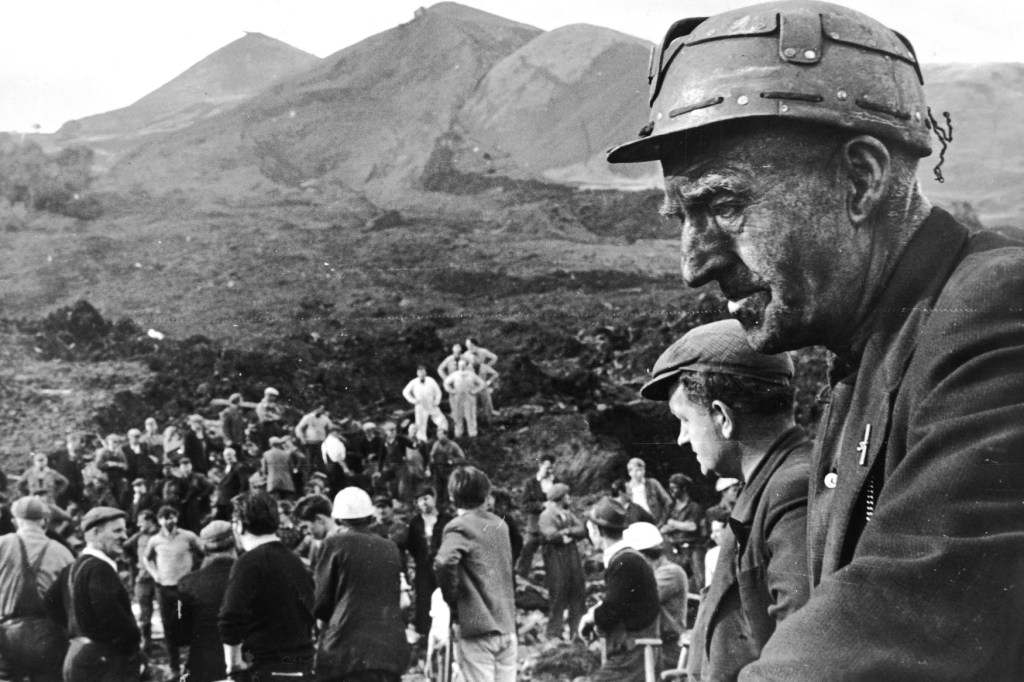

Aberfan: A single word, the name of a small village in the county of Glamorgan, Wales, which will bring immediately to mind, not only to we who are Welsh, but to millions worldwide, a single tragic picture – that of the great deluge of black slurry which at 9.13 a.m. on the morning of 21st October, 1966, slid down a hillside, engulfing everything in its path and cutting short the lives of 144 people, most of them children, as they began a new day. It is a name and an event printed indelibly on so many minds, that day on which a colliery spoil tip perched high above Aberfan stirred its unstable roots and sent a torrent of more than 150,000 tonnes of coal waste tumbling upon the village school and part of a row of houses. Here, guest-poet Gwyn Owen looks back upon the tragedy after some forty years had passed and with the lyrics of his song, Come Dance Away The Shadows, paints an inspirational picture in words. Gwyn is a writer of short stories, poems, songs, and plays. He has also written a screenplay and a young-adult novella. From his own memories, especially of that day on 21st October, he tells us:

‘I was born in Pontypridd, a town a few miles south of Aberfan, as were my parents. We left there for the then new town of Cwmbrân when I was three. But, as most of my relatives continued to live in and around Pontypridd, I visited often and always had a strong emotional attachment to the area. I was thirteen when the shadow of the Aberfan disaster darkened our lives. I will always remember how I heard of the tragic events for the first time. I was off school on the day (the half-term holidays were different in Cwmbrân and Aberfan) and that morning, my mother, as she often did, was listening to the radio. It was the BBC Home Service, which in those days broadcast through the medium of Welsh for a couple of hours a day. Although I was aware my mother listened to the Welsh broadcast, I had no Welsh myself, so paid little attention to the fact. I remember asking my mother something and her ignoring me, instead, turning to the radio and listening a little more intently. I asked my question again, a couple of times, before my mother turned to me and snapped ‘Shut up!’. Snapping at me was something she never did. Shocked, I watched her turn toward the radio again, listening intently. The tears slowly started to trickle down her cheeks. She didn’t stop crying for a few minutes, unable at the time, to tell me what she had heard. What has stayed with me ever since was, of course, the news of the tragedy itself; but also the fact that I was unable to understand my own language’.

Before coming to Gwyn’s poem, a brief overview of what others have said: because much has been written of the Aberfan disaster in verse. Notably, among others in Welsh, are poems by D. Gwenallt Jones and T. Llew Jones. In English there has been a good deal more – poems by natives of Aberfan who were there on the day, some of them relatives who, when the cataclysm came, were working their shifts underground; poems by later witnesses who assisted with the rescue operations and others, natives and strangers, who many years later were moved to put pen to paper – score upon score of all of these, from which collections have been made and published. Not many of whom wrote these were accustomed to their undertaking; but what is visible in them, as individual expressions of care and grief, is their deep heartfelt sincerity. Practised poets, also in their varying degrees of ability and technique, have made their contributions; there were ‘commissions’ to write poems for the magazine-media; similarly there were the sponsored projects of arts foundations. People are composing verse on the tragedy to this day. And for those who were most fully impacted by what occurred at Aberfan, those families which lost their loved ones on that October day, the story was to be drawn out – in the Tribunal Inquiry of the following year, and its unsatisfactory and questionable repercussions which dwell still in Welsh minds. [For succinctness, perhaps the best assessment of the legalities of the situation regarding corporate responsibility is ‘All the elements of tragedy were there’posted by Environment, Law, and History on October 24, 2016. The title is a variation of the refrain from Keidrych Rhys’ poem Aberfan: Under the Arc Lights ].

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Come Dance Away The Shadows

In the quiet of the evening I hear their voices call

Come dance away the shadows one and all

Watch the fortress crumble and the highest mountain fall

Come dance away the shadows one and all

In the quiet of the evening their spirits walk abroad

Dancing with the spirit of their Lord

They offer you no promises that morning sun can’t keep

And dance away the shadows as you sleep

They call like children playing from a summer meadow green

They dance and sing like time has never been

All memory has faded and tomorrow never comes

And dance away the shadows one by one

You who fear the demons with hatred in their eyes

The prophets with their sermons and their lies

Hear the whispered voices of the children as they call

Come dance away the shadows one and all

Out there in the forest they evil shadows steal

And knowingly sing ‘all who suffer heal’

The lamb will tame the lion and the tyrant with his gun

And dance away the shadows one by one

In the quiet of the evening I hear their voices call

Come dance away the shadows one and all

Watch the fortress crumble and the highest mountain fall

Come dance away theshadows one and all

Gwyn Owen

© 2024 Gwyn Owen. All rights reserved

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Those who have read a fair portion of the probably hundreds of poems inspired by Aberfan will like as not conclude that the majority present stark, emotive narratives evincing all the sorrow, devastation and helplessness surrounding this unbelievably horrific disaster, ‘Why?’ ‘Why?’ is the unavoidable, omnipresent question asked by the authors of these poems, and struggle to answer in their various ways. Speaking of his lost son, one of the many moved to record their feelings in verse says: ‘He is out playing somewhere’. And it can indeed be said that when we lose a loved one, they never quite seem gone, but perhaps somewhere hidden from us, as we are hidden from them, and they exist always in our thoughts, exactly as we remember them. We, far away now in time and many of us in distance, cannot truly know the suffering following that day. How in heaven’s name can those who were directly affected come to terms with what happened? Some illusory, hardly conceivable measure through which a kind of conciliating chapter may be reached must be all there was and is to hope for.

Come Dance Away The Shadows takes a singular approach to this grief. As a song it has a harmony drifting through it which carries us to and among the lost children, yet away from a heaviness of thought. It might occur that the picture is very much like another, and one we all know, concerning children taken into a hillside – those said to have been following the piper’s tune in the village of Hamelin seven hundred years ago. This has been noted before; it is a feature of T. Llew Jones’ Welsh poem mentioned above, and has been again noted by others in the mass of Aberfan poetry. The parallel is a relevant and poignant one, from the number of children – 130 in Hamelin – in that the German account is thought to be based on an actual event, and in that the children were taken by the mountainside. It is as though, in Gwyn’s song, the children are calling out to us in reassurance; they will dance away the shadows left on their loved ones’ and remaining lives ‘as we sleep’. In two of the later stanzas there is a note of unease, a sombre note which might lead us to the thought that their passing was indeed avoidable; or perhaps a reminder of how little account the demons which sometimes inhabit adult minds, when all life and love is taken into account, need be. The song is a gentle calling, and we are asked to listen for the voices in the hope that in our recollections we can know a child’s peace.

Dau gerdd / two poems for the Eisteddfod Gogledd America Welsh Language Poem (Adult) Anadl y Ddraig Clychau Cymru Yn llawen iawn mae’r gân yn son Am glychau’n canu dan y don Ond yn isel iawn yn gorwedd Cantre Gwaelod a wnaeth ei fedd. Clychau Aberdyfi chwe waith; Six Bells aeth â glowyr i’w gwaith Bwrodd tanchwa ei hergyd nwyol Ar y glowyr, ergyd farwol. Yn y pyllau roedd bywioliaeth Cydblethiad bywyd a marwolaeth Trist oedd y clychau, yn eu cân I blant a gollwyd yn Aberfan. Tramor, mae’r clychau’n llawenhau Yn galw ar y bobl i’w dathliadau Ond mae ein clychau ar y gwynt Yn canu am golledion, amser gynt. English Language Poem (Adult) Dragon Tongue The Bells of Wales In merry tones the tale we tell Of bells that ring below the swell; But ’neath Aberdyfi’s waves Lie Cantre Gwaelod’s watery graves. Six times rang Aberdyfi’s bells Six Bells, the coal mine in the dell Where firedamp struck a killing blow And claimed the miners deep below. A livelihood was in the mines; But life and death they intertwined: The bells rang woeful, sad, and long For children lost at Aberfan. So oft we hear as joyful bells Of victories, worship, weddings tell; But Welsh bells ring of long ago For all we lost, who lie below.

>

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, red dragon: Yes, ‘Clychau Cymru’/’The Bells of Wales’ was on my mind, too, when I posted Gwyn’s song.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I posted this on my blog 11 years ago.

https://stgregoryschurch.typepad.com/stblogorys/2013/08/prayer-in-time-of-trouble.html

Do not get lost in a sea of despair.

Do not become bitter or hostile.

Be hopeful, be optimistic.

Never, ever be afraid to make some noise and get in good trouble, necessary trouble.

We will find a way to make a way out of no way.

John Lewis, June 2018

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reading and commenting on ‘A Song for Aberfan’, Bill. Words to dwell on and to encourage, from St. Blogory’s.

LikeLike

I love the haunting melody of this poem.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, there’s a captivating, conciliating threnody coursing through it all, We can hear their voices.

LikeLiked by 1 person